【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 17 : The Colors of Kabuki – White / Narrated by Tateo Okido

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 17 : The Colors of Kabuki – White

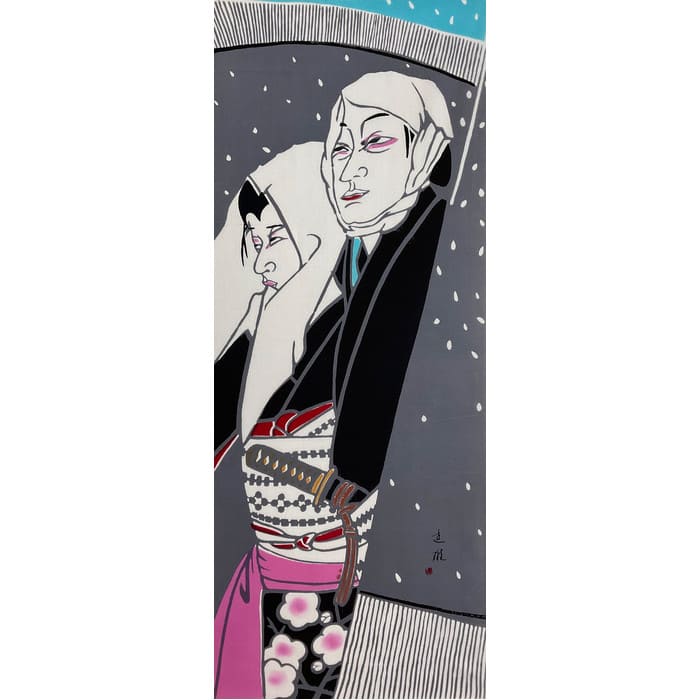

There is a quiet elegance in the sight of snow gently falling on a kabuki stage. Though made of simple triangular paper slips, the snow evokes the chill of a wintry roadside and stirs the emotions of the audience.

On stage, a white cloth known as yukinuno is laid down to suggest a snowy ground, while snow-covered trees and painted mountain backdrops recreate the beauty of a silvery landscape.

Scenes such as the meeting of Naozamurai and Jōga at the soba shop in Kumoni Magō Ueno no Hatsuhana, or the farewell in Koi Bikyaku Yamato Ōrai at the Ninokuchimura-village, are steeped in a uniquely serene pathos. Interestingly, the Ninokuchimura-village scene was originally set in the rain and mud. Over time, it was changed to snow for aesthetic reasons — a decision that reflects kabuki‘s visual priorities. While rain suggests tears and farewell, snow’s silent fall evokes a deeper, more poignant beauty. Compared to the steady drip of rain, the hushed descent of snow penetrates the audience’s heart more profoundly.

Snow in kabuki often intensifies emotional partings — between parent and child, between bride and in-laws — emphasizing loyalty, love, and sorrow. As the snow falls more and more heavily, it wraps the scene in a visual poetry that kabuki does so well. The color white, in these moments, becomes a symbol of purity and spiritual intensity, blanketing everything in quiet solemnity.

In the kabuki play Sono Mukashi Koi no Edozome, Oshichi climbs the fire watchtower and beats the drum in a passionate outcry of love. The falling snow seems to echo her inner flames — a unique kabuki inversion where the fire of emotion is rendered in white. The same holds true for the iconic dance piece Sagi Musume (The Heron Maiden). Both are set in snowy worlds, where the characters’ sorrow, love, and beauty shine even more brightly.

In kabuki’s aragoto (rough-style) roles — like Kamakura Gongorō in Shibaraku or Asahina in Kotobuki Soga no Taimen — white is used in chikaragami, sacred folded paper strips attached to the actors’ topknots. These resemble ritual paper used in Shinto practices and symbolize courage. The color white, with its connotations of purity and sanctity, also conveys a spiritual, almost mystical power. More than just a costume element, it reflects Edo kabuki’s unique aesthetic: a theatrical form where the common people found hope not in samurai, but in divine heroes portrayed by actors. In this way, kabuki absorbed and stylized elements of folk religious traditions.

And one must not forget the flowing white hair in Shakkyo-mono plays. In works like Kagami Jishi and Renjishi, the lion spirits perform a movement known as arai-gami (“hair-washing”), in which the long mane is flung forward and shaken side to side. The hair brushes the stage as it swings, giving the illusion of washing. The climactic spinning movement, where the mane whirls in a dramatic flourish, is called tomo-e.Th e powerful latter half of Kagami Jishi, choreographed by the great Ichikawa Danjūrō IX in the Meiji era, evokes a sacred ritual in its solemn intensity.

Unlike earlier shishigashira dances, Danjūrō’s version suited the refined tastes of modern audiences, and was later passed down through the Otowaya lineage, notably by Onoe Kikugorō VI. His style became the definitive version of the dance, inherited by Kikugorō VII, Baikō VII, the current Kikugorō and Kikunosuke, and from Nakamura Kanzaburō XVII to XVIII, and now to the current Kanzaburō. The white-maned lion dancing before red and white peonies remains one of kabuki dance’s greatest achievements. When French artist Jean Cocteau saw Kikugorō VI perform Kagami Jishi in 1936, he famously said, “A god has descended.” This deeply spiritual artistry is recognized worldwide.

From falling paper snow to wigs and makeup, the color white in kabuki carries a sacred, symbolic weight — a colour of beauty, emotion, and spiritual resonance.

」.jpg)