【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 5 : Imitation / Narrated by Tateo Okido

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

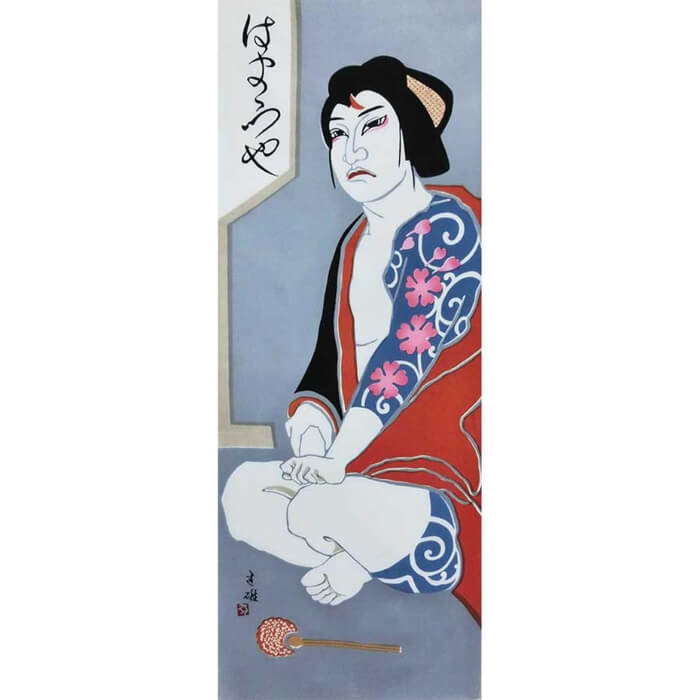

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 5 : Imitation

A while back, a television show called Kasō Taishō (“Costume Grand Prix”) became popular. It featured people performing visual and physical imitations of various objects, scenes, or ideas. In earlier days, there was a performing art known as seitai mosha (vocal mimicry), in which people imitated the voices and mannerisms of well-known politicians, business leaders, and celebrities. At year-end parties and New Year’s gatherings, there was always someone who would perform this kind of mimicry.

In the Shōwa era, people would often compete in imitating the famous intonations (kowairo) of great Kabuki actors, especially when performing iconic lines like “Shiraza— itte kikasemashō” or “Tsuki wa oboro ni shira-uo no” or “Owakē no, omachinasē.” These lines, delivered in the rhythmic shichigochō (7-5 meter), were associated with acting houses such as Otowaya, Tachibanaya, and Harimaya, and mimicking them was a source of both admiration and entertainment.

Setting aside today’s legal concerns around copyright and likeness rights, I believe that gei (artistry) begins with imitation of the masters. Many actors, as seen in their autobiographies and interviews, have shared how they would “steal” the techniques of great performers by watching them from behind the curtain, then interpret and practice them on their own.

Today, it is more common for younger actors to study directly under seniors they respect, learning the traditions of their acting houses. There is also a growing openness in mentoring actors regardless of lineage, in the hope of preserving the Kabuki arts. But in earlier times, there were no mentors who would teach with such care. Even though Edo Kabuki has an element of inheritance, even between parent and child, once on stage, they were considered professional rivals—fiercely competitive equals.

He also likely absorbed the artistry of his maternal grandfather, Onoe Kikugorō VI, and his paternal grandfather, Karoku, from the Harimaya line. On the foundation of this classical training, he went on to shape a new, modern Kabuki and became a star full of presence and originality. It was heartbreaking that illness struck him just as he was reaching for even greater heights. But those who follow in his footsteps should recognize the depth of his dedication.

Of course, appearing frequently on television and in media, and building relationships across artistic genres, is also important. But the question remains: what elements do you incorporate into your own gei, and how clearly do you define your artistic goals? This calls for a firm resolve.

I hope those involved in traditional arts do not stop at mere monkey-like imitation, but instead absorb the spirit and artistic domain of the masters they trust—and strive for ever greater artistic heights with conviction and discipline.