【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 14 : Igami no Gonta / Narrated by Tateo Okido

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

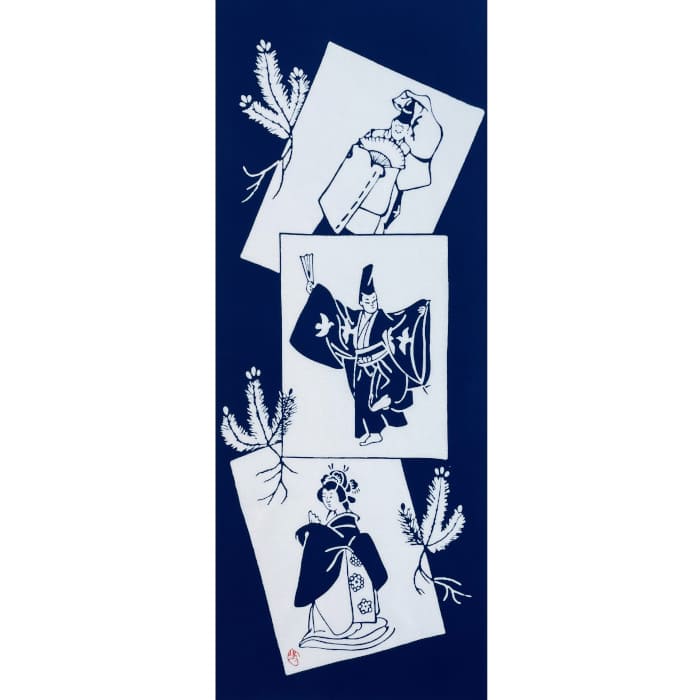

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 14: Igami no Gonta

“You’re being such a gonta, no snacks for you!”

“My little gonta is a real handful — makes me cry sometimes!”

These were the kinds of phrases the author often heard growing up in Kansai.

In the Kansai dialect, gonta refers to a child who throws tantrums or won’t listen — the kind of mischievous, willful child every parent has dealt with. Over time, the word evolved to describe a generally unruly or stubborn personality.

But did you know the word “gonta” actually originates from kabuki? Specifically, from the character Igami no Gonta, who appears in the third act of Yoshitsune Senbonzakura — in the scenes known as Shii no Mi and Sushiya. The name “Igami” itself is derived from “yugami” (twisted or warped), a reflection of the character’s devious nature.

The third act of Yoshitsune Senbonzakura is a fan favorite, especially for its dynamic theatrical style. There are two major interpretations: the Kansai (Osaka) style, which emphasizes rusticity and humor, popularized by actors like Jitsukawa Enjaku and Nakamura Ganjirō; and the Edo style, known for its brisk, stylish delivery — especially the beranmee speech patterns of the Kiku-gorō lineage. The contrast is perhaps most vividly seen in how Igami no Gonta is portrayed.

The Edo-style Gonta, crafted by the legendary 5th Matsumoto Kōshirō (also known as “Hanataka Kōshirō” for his distinctive nose), was passed down to the 3rd Onoe Kikugorō, then to the 5th, and finally perfected by the 6th Kikugorō, whose interpretation remains the standard today. Though the story is set in Yamato (modern-day Nara Prefecture), Gonta is rendered as a quintessential Edokko — brash, charming, and rough around the edges.

A touch of flair and sensuality is essential to this role. In the Shii-no-mi scene, Gonta picks a fight with Kokingo and swindles him out of 20 ryō (roughly equivalent to several thousand USD today). His scam and swagger make him feel like a low-level gangster — sharp and dangerous. One highlight is when Kokingo draws his sword, and Gonta, in a low squat, calmly blocks him with his left foot — a move that thrills audiences with its bold theatricality.

But Gonta is more than just a thug. When he reunites with his wife and young son, who work at a tea shop, a softer side emerges. If played too heavy-handedly, the scene loses its charm. But done right, the glimpse of happiness — the smile of a husband, the warmth of a father — creates a touching contrast with the rogue we saw moments ago.

Deep down, Gonta isn’t a true villain. He’s a spoiled son from a good family, led astray by his own indulgence. This comes through most strongly in the Sushiya scene. There, he switches a bucket meant to contain Kokingo’s head with another, and manipulates money from his mother. Yet even in these deceitful moments, glimpses of love and loyalty for his parents shine through.

In one climactic moment, Gonta dashes across the stage with a sushi bucket and strikes a dramatic pose on the hanamichi. In the Edo tradition, following the precedent of the 5th Matsumoto Kōshirō, the actor adds a small mole above Gonta’s left eyebrow — a symbolic touch.

Many theater critics have long preferred the Edo-style interpretation of the third act. The influential dramatist Kaoru Osanai once claimed that Gonta’s tragic arc is the emotional heart of the entire play. In fact, he went so far as to say that even if all other scenes vanished, Gonta’s would remain unforgettable. (As noted in Kabuki Quarterly, Issue 9, Shunjiro Aoe’s essay: “The Evil of Gonta.”)

」.jpg)