【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 7 : Makuai / Narrated by Tateo Okido

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

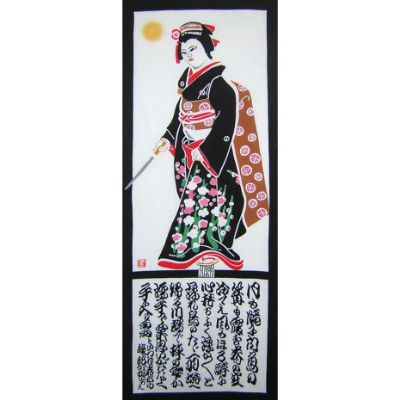

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 7 : Makuai

Some people pronounce it makuma, others makuai, but I was told by an elder that the correct reading is makuai—referring to the interval between acts in a kabuki play. While the stage crew is scrambling behind the scenes to prepare the next set, black-clad assistants move swiftly and precisely like clockwork.

For the audience, however, it’s a break—time to use the restroom, have a meal, or stroll through the theater.

In earlier times, this makuai was treated as personal time by theatergoers. If their favorite actor wasn’t in the next act, they might return to their designated tea house (shibai jaya) to dine, drink, or even invite the actor over for conversation. For theaters, it was a blackout period needed to prepare the next stage set. In Edo, this intermission time was announced, but in Kamigata, it wasn’t—once the stage was ready, a clapper (hyōshigi) would signal the next act’s start.

Today, intermissions are generally fixed at 25 or 30 minutes and strictly managed by the theater. When time is up, staff come around with large plastic bags to collect lunch boxes and trash. This may be efficient and beneficial for the theater’s scheduling, and many younger patrons seem to accept it. It’s also true that scene changes during blackouts have become remarkably streamlined. But we should ask—who exactly is this efficiency for: the audience, the performers, or the theater?

Attending the theater should be an escape from the everyday. It’s about entering a festive, otherworldly space—and audiences pay no small amount for this experience. If there’s no time during intermission to savor that atmosphere, it feels like something has been lost. I believe the theater should guarantee patrons the right to enjoy unhurried personal time and space. The current system feels like it robs us of that freedom.

At the Naka-za in Dōtonbori, Osaka, and the Minami-za in Kyoto, there used to be cozy little oden stalls inside the theater, run by friendly older couples like something out of a rakugo story. During makuai, I’d order one or two skewers and a warm bottle of sake, and soak up all kinds of information from seasoned kabuki fans sitting nearby. These were ordinary folks, but surprisingly knowledgeable and discerning—a kind of grassroots critic. This created an atmosphere where kabuki truly felt like a form of entertainment nurtured by the people, a living cultural tradition.

I hope we can revive such rich, immersive spaces in Japanese theaters again—places where time slows down and culture breathes.

Our tenugui are available at the Kabuki-za gift shop. Be sure to stop by during the makuai intermission and take a look!

」.jpg)