【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 6 : Yatsushi Style / Narrated by Tateo Okido

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 6 : Yatsushi Style

In Kabuki, one of the role types is known as wagoto—a gentle, romantic style. This category of roles often involves elements like nuregoto (love scenes), yatsushi-goto (disguise or downfall roles), and irogoto-shi (the art of seduction). In the Kabuki plays we see today, such roles appear in characters like Shinbei the sake seller in Sukeroku (who is actually Soga Jūrō Sukenari), Chūbei in Koi Bikyaku, Jihei in Kamiji, and Izaemon in Yūgiri. These roles depict men who are soft-spoken yet refined—more akin to modern “herbivore men” than muscular, rough types. Still, they are portrayed as sincere, emotionally resilient, and full of inner dignity and class.

The verb yatsusu means “to alter one’s appearance” or “to humble oneself,” and originally described someone of noble or wealthy birth who, having fallen into ruin through extravagance or misfortune, now lives in a degraded state. But in the world of Kabuki, even when portraying such a downfall, the actor must express the character’s original elegance and charm.

The earliest master of yatsushi-goto was said to be Sakata Tōjūrō, a celebrated actor of the Genroku era, known as “the master of yatsushi roles.”

A prime example of yatsushi-goto is the Yoshidaya scene in the play Kuruwa Bunshō, often performed by Kamigata-style actors. Commonly referred to as Yūgiri Izaemon, the play tells the story of a tayū (high-ranking courtesan) and her fallen lover. In Kabuki, well-known plays are often referred to by their lead characters rather than their full titles. Interestingly, when a man and woman are involved, the woman’s name usually comes first—Ohatsu Tokubē, Osome Hisamatsu, Ohan Chōemon, Yūgiri Izaemon, Umekawa Chūbei, and so on. Why is this? Perhaps in matters of love, even in a male-dominated society, women took emotional precedence.

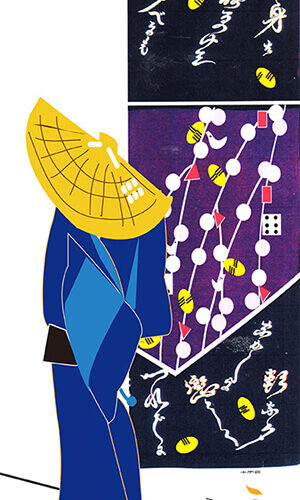

Returning to Yoshidaya: the staging of yatsushi-goto here is highly refined. Izaemon appears on the hanamichi in a straw hat and a paper kimono (kamiko). A stage assistant (kurogo) offers a candle (tsura-akari) to illuminate his face. This young master, once dressed in luxurious silk, now appears tattered and poor. Yet once the stage lights brighten, the design of his paper robe reveals a refined aesthetic—its form, its colors (especially purple), all reflect the graceful elegance of a wealthy merchant’s son, embodying the Kamigata sense of beauty.

While waiting in the guest room for Yūgiri, Izaemon acts playfully and light-heartedly, gradually transforming from a man in ruin back into the gentle, elegant lover in a keisei-goto (courtesan romance) role. The play ends on a cheerful note, with his family pardoning him and a chest of 1,000 gold coins arriving to ransom Yūgiri—a simple and heartwarming resolution.

Through this single love story, the stage captures the aesthetics of keisei-goto, yatsushi-goto, nuregoto, and irogoto-shi—a slice of Genroku-era romantic drama, both radiant and enjoyable.

Tenugui Design “Yoshidaya” – Original Artwork by Tateo Okido