【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 4 : A Side Note / Narrated by Tateo Okido

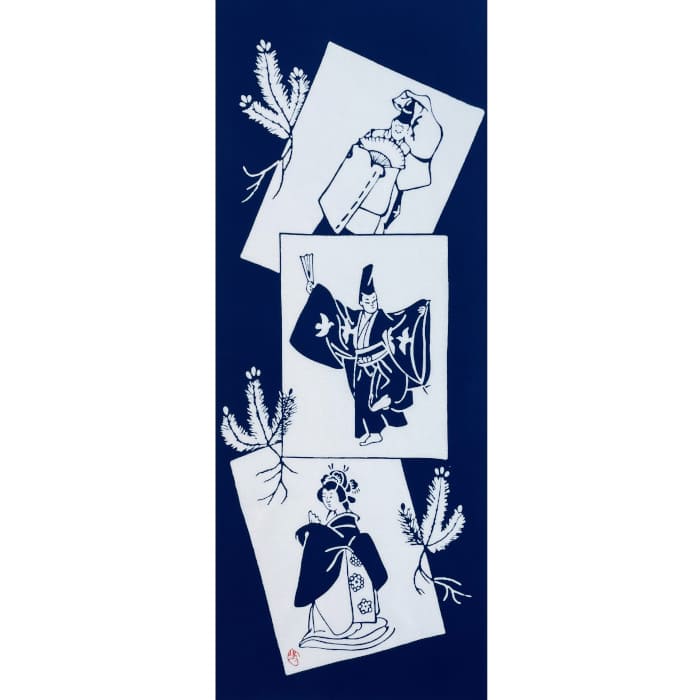

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 4 : A Side Note

In recent years, stage productions such as Cocoon Kabuki, Super Kabuki II, Roppongi Kabuki, and Akasaka Kabuki—featuring young Kabuki actors—have frequently been staged. These performances are full of fantastical plots, manga-like visuals, speed, and glamour.

Alongside this creative explosion, I sense a certain cultural looseness—a result of the Meiji-era modernization and post–World War II education. Traditional Japanese ways of thinking and emotional expression have gradually faded, replaced (for better or worse) by ideologies of liberalism and democracy that have taken root in the Japanese consciousness.

With the end of the Shōwa era and the beginning of Heisei, Japan has undergone rapid transformation. The rise of computers and other new media has ushered in an information society, altering how people communicate and bringing change—even to historically rooted cultural traditions like Kabuki.

Over the past 30 years or so, it’s clear that the landscape of stage arts has shifted significantly. In Kabuki as well, we now see experimental direction, collaborations with newly formed theater groups, and scripts inspired by television and manga. New styles of performance are increasingly defining the contemporary Japanese theater scene.

During the modern Kabuki era, such innovation was not unusual. In the Meiji period, for example, Ichikawa Danjūrō IX introduced the katsureki-mono genre, and new Kabuki works were created by popular novelists of the time. Kabuki has always evolved with the times, driven by actors’ efforts to reform and innovate. Many masterpieces were born from this spirit. Yet today, those masterpieces are staged less frequently—likely a reflection of changing public tastes.

Among today’s young actors, it is undoubtedly Ichikawa Ennosuke III (now En’ō II), the pioneer of Super Kabuki, who serves as a guiding star. He was followed by Nakamura Kanzaburō XVIII, whose fresh sensibilities brought new life to Kabuki. And yet, both were deeply rooted in the 400-year-old traditions they inherited.

Since the beginning of the Heisei era, however, the Kabuki world seems to be splitting into two streams: one continuing classical Kabuki, and the other staging Kabuki-style performances. This divide is evident in the sharp decline of productions that faithfully portray the heart and spirit behind the traditional roles and forms passed down through generations. Moreover, attempts to interpret those traditional plays in ways that reflect the present age are increasingly being neglected.

Commercial theaters, much like TV broadcasters chasing ratings, prioritize productions that feature popular actors or flashy, unconventional staging. These often fail to connect to the legacy of Kabuki’s classical artistry. Some performances use only superficial elements—like dramatic mie poses or keren (stage tricks)—to dazzle the audience. Such productions exaggerate these techniques as if they alone define what Kabuki is.

Today, younger Kabuki actors are being encouraged to prioritize these attention-grabbing styles, backed by theater producers. But to me, these performances seem to belong more to the margins of Kabuki’s historical narrative—a mere appendix, rather than the core of the art form.

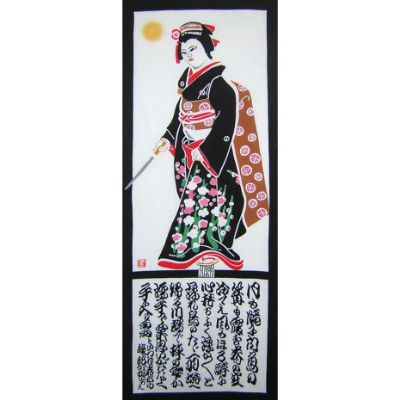

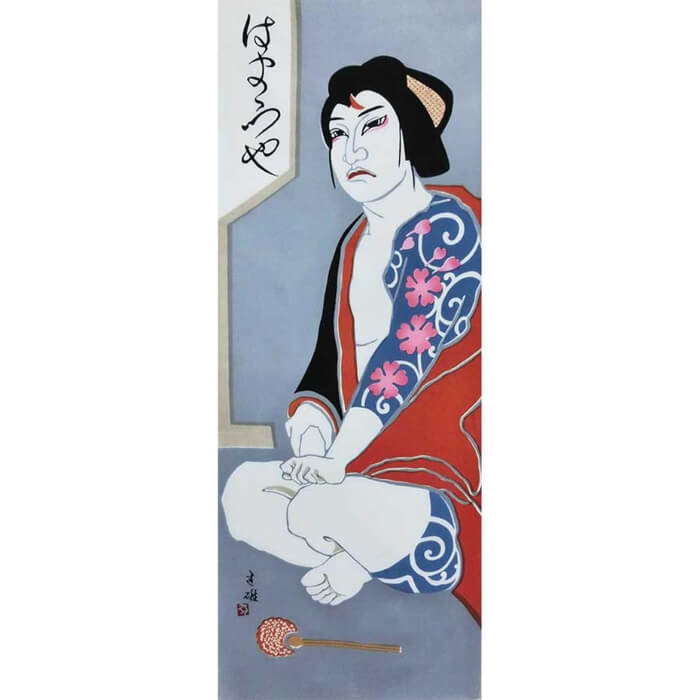

Tenugui “Sukeroku” – Original Artwork by Tateo Okido

View the product page here >> Shop Now

」.jpg)