【KABUKI Miscellany】 Episode 2 : Samurai and Townspeople / Narrated by Tateo Okido

Hello! We are Asanoha, a tenugui specialty shop located in AzabuJuban, Tokyo.

We’re delighted to share a collection of intriguing stories related to Kabuki. These tales are narrated by Mr. Tateo Okido, an expert in Kabuki and the artist behind the original designs of our Kabuki-themed tenugui. Please enjoy this special series, Kabuki Miscellany, presented by Mr. Okido.

Kabuki Miscellany – Episode 2 : Samurai and Townspeople

During the Edo period, society was structured with samurai at the top of the hierarchy, followed by chōnin (townspeople) who lived in cities, and hyakushō (farmers) in rural areas. The population of Edo was dominated by samurai, whereas the Kyoto–Osaka region (Kamigata) had a higher density of chōnin. Naturally, a warrior culture developed in Edo, while a merchant culture thrived in Kamigata.

This distinction is also reflected in Kabuki. Edo Kabuki is known for its dynamic, bold style called aragoto (“rough style”), while Kamigata Kabuki is known for its softer, more romantic wagoto (“gentle style”). The founders of these two styles are well known: the first Ichikawa Danjūrō in Edo, and the first Sakata Tōjūrō in Kamigata.

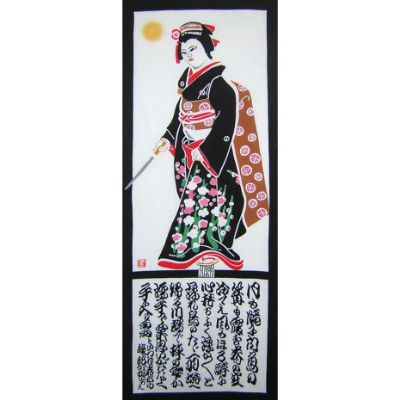

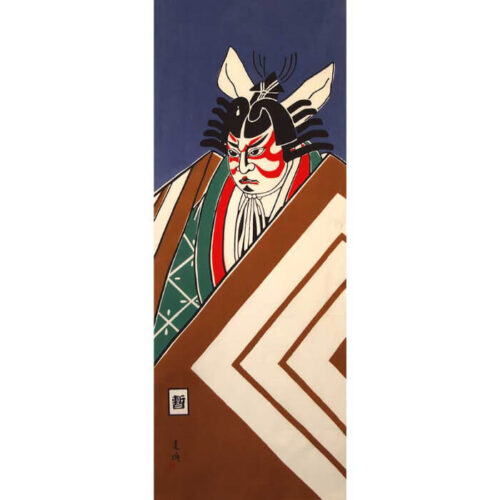

The aragoto of Edo is loud and vigorous, characterized by expressions like “Yattoko-tocchā, yattoko-nā!” conveying strength and bravado. These plays often feature larger-than-life heroes with the wild charm of mischievous boys, set against backdrops filled with suits of armor, swords, spears, rocks, and stone walls — all projecting a strong and solid atmosphere.

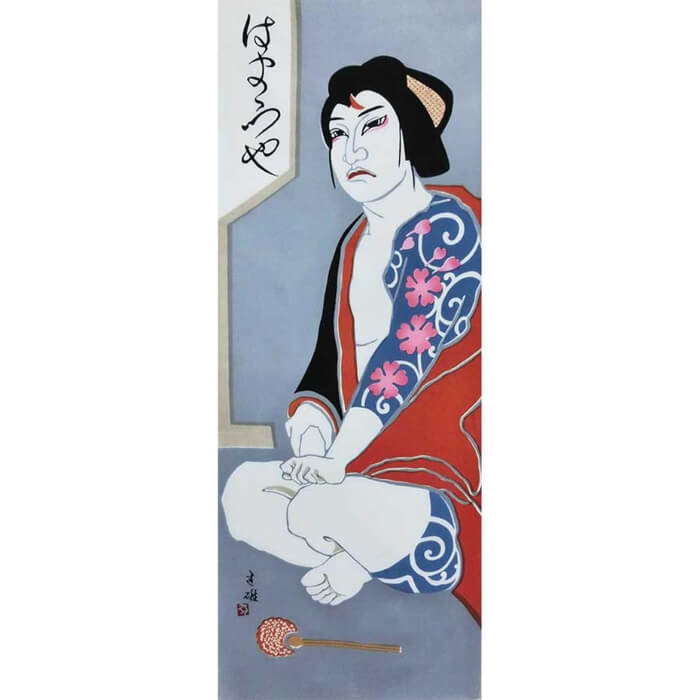

In contrast, Kamigata Kabuki presents delicate characters like Kamiya Jihei, who walks onto the hanamichi in a trance-like state to the soft rhythm of takemoto music, or Fujiya Izaemon, waiting longingly for the courtesan Yūgiri. These characters, often known as tsukkorobashi (naïve young men), are gentle, effeminate types who radiate a quiet sensuality — the wagoto style evokes a soft, graceful world with the rustle of silk and fluttering tenugui.

Edo, the home of the shogunate and samurai culture, and Kamigata, the economic center of Japan with its merchant-driven society — these differences in environment naturally influenced the creation of Kabuki narratives and performance styles.

In its early days, Edo Kabuki featured comical sketches by Saruwaka Kanzaburō, an actor who had come from Kamigata. But it was Ichikawa Danjūrō I, himself believed to be born into a samurai family, who paved the way for aragoto Kabuki. His secret acting motto was to “perform with the heart of a child,” portraying characters who were big-hearted, brimming with a sense of justice, and champions of good over evil — the kind of upright hero that the people of Edo envisioned as an ideal samurai.

Meanwhile, Kamigata Kabuki, rooted in ningyō jōruri (puppet theater), developed through stories of emotional complexity — featuring the relationships between masters and servants, parents and children, financial hardship, and romantic entanglements. These plays unfold within a world of duty (giri) and emotion (ninjō), where characters grapple with very human dilemmas, making the stories feel more realistic and relatable.

Edo Kabuki delivers a bold, cathartic experience with a refreshing sense of justice, while Kamigata Kabuki touches the heart with emotional depth and a lingering tenderness that celebrates the human condition. I hope the younger generation of actors will carry forward these traditional qualities of both styles.

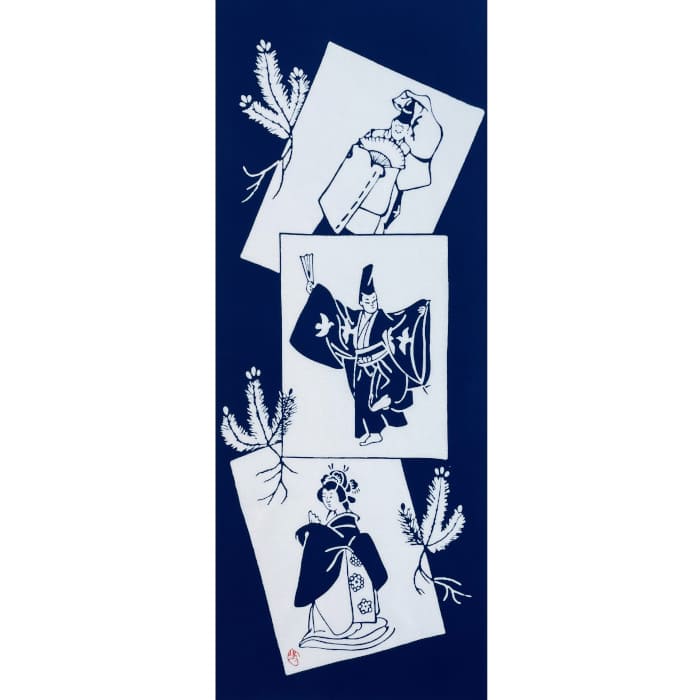

Tenugui designed from original artwork by Tateo Okido

Iconic Edo Kabuki Performance: Shibaraku

Representative Kamigata Kabuki Performance: Kawashō (Kamiya Jihei)